Lingchi – The Centuries Old Cut-By-Cut or Slow Slicing Torture Tactic

Lingchi was an age-old Chinese torture and execution tactic inflicted as a capital punishment for crimes considered severe like treason, mass murder, matricide and patricide. Translated loosely as slow slicing, the lingering death, the slow process and death by a thousand cuts, the terrifying punishment, which was also given in Vietnam, included a long and slow torture process of methodically removing portions of body with a knife for over a period of time resulting in death. It prevailed in China from around 900 CE till the time it was banned in 1905.

What is Lingchi?

Lingchi was a form of capital punishment in China that widely existed from around 900 CE when the Tang Dynasty was in power till it was officially outlawed in 1905 toward the end of the Qing Dynasty. Perhaps the most brutal and dreaded ancient torture and execution tactic in the history of mankind, Lingchi was imposed on those lawbreakers who were considered to have committed severe crimes like treason mass murder, matricide, and patricide. This brutal and cruel punishment process that eventually led to death of the lawbreaker involved administering a number of cuts to the skin and removing body portions of the lawbreaker methodically with a knife to see the number of cuts the lawbreaker can bear and give him a long and slow torturous death. Families who managed to pay bribe had the relief of seeing their relative killed by a stab at the heart right away instead of going through hours of brutality resulting in death. The punishment was also meted out on family members of enemies and on some Westerners. Lingchi is thus aptly translated loosely as slow slicing, the lingering death, the slow process and death by a thousand cuts. Although such punishment method was banned in the early 20th century, the very concept of Lingchi continues to feature in different media.

(Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi, https://allthatsinteresting.com/lingchi)

How did the term Lingchi Originate?

The term Lingchi found its mention for the first time in a line in Chapter 28 of the ancient Chinese collection of philosophical writings called ‘Xunzi’ that was attributed to the 3rd century BC philosopher Xun Kuang. However, originally the line elucidated the hardship of travelling across a hilly terrain in a horse-drawn carriage. It was later applied in expressing the extended anguish and suffering of a person while being executed.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi)

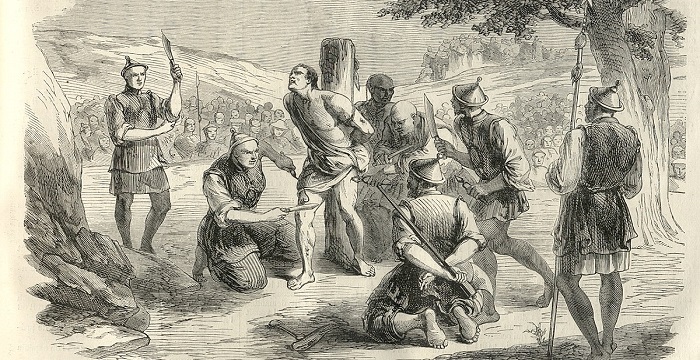

Image Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi

What’s the procedure of Lingchi?

In Lingchi, a convicted prisoner would be generally tied up to a wooden frame in a public place. As per reports of Qing dynasty jurists like Shen Jiaben, as the convention of performing Lingchi was not particularized in the penal code, the customs of the executioners differed. However, even though the exact procedure was not elucidated in detail in the Chinese law, the practice involved cutting several slices of flesh from the body of the prisoner. The punishment was inflicted on the law breaker for committing severe offences, such as high treason, murder of one’s master or employer, mass murder, and patricide and matricide. It was not only used as a form of public humiliation for the prisoner who would be given a slow and lingering death but was also applied as an act of indignity and embarrassment for the prisoner even after death. Slicing body parts meant that the prisoner’s body would not be whole even in the spiritual world post death. This, however, contradicted with the Confucian principle of filial piety where cutting or altering body are regarded as unfilial practices.

The cruel practice was used both for tormenting and executing alive as well as for degrading the mortal remains of a person. The emperors used the practice as a weapon to intimidate and scare people, and at times imposed it for even minor offenses. They ordered the punishment even on family members of enemies. Even a three days incision was ordered by some while many gave orders for certain tortures prior to execution else for a lengthy execution. This is manifested by arrest and subsequent execution by lingchi of politician, military general, and writer Yuan Chonghuan, who served under the Ming dynasty. His screams were heard for half a day before he succumbed to the practice. Forced convictions and unjust or illegal executions also became part of the game. Although the precise details on the way Lingchi was conducted are hard to obtain, the process usually involved a series of cuts on the chest, arms and legs followed by amputation of limbs before stabbing the heart or decapitating the victim resulting in death. In case the victim fell on the hands of a merciful executioner or the offense was considered less severe, the throat would be cut first leading to death of the victim following which the body would be subjected to several cuts mainly to dismember it. In case the family of the victim could manage a bribe, the coup de grâce would be applied, stabbing the heart first, thus killing the victim right away, which saved him from the gruesome and lingering torturous process before death. Possibly the victims’ flesh were also sold as medicine. Slicing of bones, and cremating and scattering the ashes of the victims might have also been part of the dreaded practice.

Pointing out to the pictures of Lingchi that are still in existence, American art historian and art critic James Elkins suggested that in such practice the victim faced some amount of dismemberment while still alive. In his opinion, the whole procedure of Lingchi could not have lasted longer for a victim, which, however, does not go in line with the questionable version of “death by a thousand cuts.” He argued that a couple of severe wounds would have made the victim unconscious, even if he was still alive. Thus the brutal practice could have included only a “few dozen” wounds and not more. The extant pictorial records of the practice, which is elucidated as an expeditious method of torture and execution not taking more than 15 to 20 minutes, also suggest the speedy nature of the process as the series of pictures of a particular event show the same crowd witnessing it. German criminologist Robert Heindl termed the process as “death by division”.

(Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi, https://allthatsinteresting.com/lingchi)

Under which Chinese dynasties Lingchi existed?

Lingchi was in force from the earliest Chinese monarchies, but torture of lesser degree was inflicted. During the rule of the second emperor of China’s Qin dynasty, Qin Er Shi (reign: October 210 – October 207 BCE), officials were punished through several types of tortures. Liu Song dynasty’s emperor Liu Ziye (reign: July 12, 464 – January 1, 466), who became notorious for his violent and impulsive acts and sexually immoral behaviour, applied Lingchi in executing many high-level officials. Emperor Wenxuan (reign: June 9, 550 – November 25, 559) of the Northern Qi dynasty executed six persons using Lingchi, while a general of the Tang dynasty An Lushan (reign: February 5, 756 – January 29, 757) used the process to kill one man. The practice also existed during the Five Dynasties period (907–960 CE).

Lingchi prevailed from around 900 CE (during the rule of the Tang Dynasty) till it was banned in 1905 towards the end of the Qing Dynasty. The Liao dynasty that ruled from 907 to 1125 also practiced Lingchi and even had a mention of the practice in its law codes. Emperor Tianzuo of the dynasty often prescribed the method to execute people. The practice was also used extensively by the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), particularly during the reign of Emperor Renzong and Emperor Shenzong. According to sources, while the condemned was tormented with 100 cuts during the reign of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), records have shown that 3,000 incisions were made by the time Ming dynasty (1368–1644) was in power.

Lingchi was applied for severe unlawful acts like treason during the later Chinese dynasties, but these charges were often questionable and made up, as in the cases of a powerful eunuch Liu Jin, and a politician, military general and writer Yuan Chonghuan, both from the Ming dynasty. Exposure of the Renyin Plot, an assassination attempt on the 12th emperor of the Ming dynasty Jiajing Emperor, in 1542 led to an order to execute a group of palace women, including the favourite concubine of the emperor, Consort Duan using Lingchi.

Apart from China, the practice was also known to exist in Vietnam. French missionary in Vietnam Joseph Marchand, who joined the Le Van Khoi revolt led by Le Van Khoi, was arrested and later executed in 1835, in Saigon using the method of Lingchi.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi)

When was Lingchi outlawed?

Shi Jingtang (reign: November 28, 936 – July 28, 942), the founding emperor of the short-lived Jin dynasty (one of the Five Dynasties), was an initial advocate against Lingchi and abolished the practice during his rule, although other emperors carried on with the punishment. Noted poet of China’s Southern Song Dynasty Lu You (1125–1210) made an early proposal to abolish the practice through a memorandum to the imperial court. The detailed argument that he put forth against the practice was later fairly reproduced and conveyed by different scholars through generations which also included prominent jurists from different dynasties. Such arguments were also included in the 1905 memorandum of Chinese politician, jurist and reformist Shen Jiaben. He along with Chinese diplomat and politician Wu Tingfang were in charge of the 1905 Qing Code revision that saw abolition of several brutal methods of punishment, including Lingchi.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi)

Which published accounts mention the practice of Lingchi?

Lingchi finds mention in various published accounts, including books, newspaper reports, and journals. These include the 1895 book of English journalist and Liberal politician Sir Henry Norman, 1st Baronet titled ‘The People and Politics of the Far East’. Norman, who travelled extensively in the East during his tenure with the ‘News Chronicle,’ gave a graphic account of the cruel practice. His collections are presently in possession of the University of Cambridge. Australian journalist George Ernest Morrison mentioned an influence of opium on the prisoner to be executed by Lingchi in his book titled ‘An Australian in China’ (1895). His writing was based on information gathered from a claimed eyewitness. The book, contrary to other reports, mentions the dismemberment of the prisoner’s body after death. Lingchi is also mentioned along with several other stories of atrocities in ‘The China Year Book’ (1927), which gives contemporary reports of fighting between the Nanjing government and Communist forces in Guangzhou (Canton). On December 9, 1927, a journalist reported for ‘The Times’ that the Christian priests were being targeted by the Communists and execution of Father Wong in public through the slicing process was announced. Other accounts mentioning use of the harsh process includes the book ‘Trails to Inmost Asia’ (1931) by noted 20th century Tibetologist George Roerich; and ‘History of Torture’ (1940) by British author George Ryley Scott.

William Arthur Curtis from Kentucky is known to have taken the first Western pictures of the practice in 1890 in Guangzhou (Canton). Around 1905, pictures of three executions through Lingchi were taken by French soldiers stationed in Beijing. These included Lingchi execution of a former official Wang Weiqin on October 31, 1904; that of presumably an unstable boy in January 1905; and of a Mongol guard Fou-tchou-li or Fuzhuli on April 10, 1905. The latter incident is regarded as possibly the last attested case of the act in history of China. Pictures of Lingchi are also found online at the Institut d’Asie Orientale (CNRS, France) hosted Chinese Torture Database.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi)

How has Lingchi been depicted in popular culture?

Many artistic, literary, and cinematic works inspired by the age-old practice have come up over time. Books by French philosopher, intellectual and literary figure Georges Bataille namely ‘L’expérience intérieure’, 1943 (Inner Experience), ‘Le coupable’, 1944 (Guilty); and ‘Les larmes d’Éros’, 1961 (The Tears of Eros) mentions about Lingchi with the latter also including five pictures of the practice. However Bataille was censured for the errors and dubious content of his work apart from the kind of language he used by historians Gregory Blue, Jérome Bourgon and Timothy Brook. The 2003 book-length essay by Susan Sontag titled ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’ that was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award also had a mention of the practice. Other literary works that referred to the Chinese practice of “death by a thousand cuts” included novels ‘Judge Dee’ by Robert van Gulik, ‘The Joy Luck Club’ by Amy Tan and ‘The Examination’ by Malcolm Bosse. Cinematic representation of the practice was featured in the 25-minute controversial film ‘Lingchi’ by Chinese artist Chen Chien-jen and in the critically acclaimed and commercially successful 1966 American war film ‘The Sand Pebbles’ directed by Robert Wise starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough and Richard Crenna among others.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingchi)